Home / Media / PPFAS in News / Parag Parikh's Big Mutual Fund Bet

Parag Parikh's Big Mutual Fund Bet

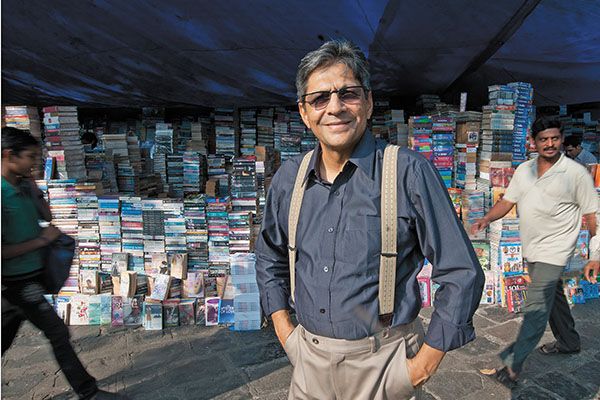

Forbes Magazine, March 5, 2013.Parag Parikh made a success of his portfolio management scheme. He is now looking to repeat his performance with a new mutual fund.

Knowing Parag Parikh

The ManA rare money manager who believes in doing the right things; business automatically follows

His Claim to Fame

Managing a PMS since 1996 with a low ticket size of Rs 5 lakh. It has given 18 percent returns ever since. Used behavioural finance to understand the boom and bust cycles of financial markets. Always been sceptical, conservative.

His Big Bet

To convert his PMS into an MF that will invest long term in Indian and foreign markets. It is expected to attract retail investors, not HNIs.

His Belief System

Buying businesses rather than stocks. Doesn’t want to play the game of assets under management. Has always been honest and committed to his clients.

Last week, Parag Parikh turned 59. In the normal course of things, it would have been just another birthday for the money manager-cum-broker, who has been active in the Indian stock markets for the past three decades. Parikh, of course, may have had a special reason to celebrate. After a three-year wait, he got permission from the markets regulator Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi) to launch his own mutual fund last October. Within the next two months, Parikh also received an in-principle approval for his scheme.

When we met him a few days later, he clearly had other ideas on his mind. On his desk was a DVD of Forest Gump, a thick tome by Ramchandra Guha and a guitar by the side of the table. “You know, I’m thinking of giving up on my cholesterol drugs. I don’t know what kind of side effects they might be having on my system. Don’t you think I should be more sceptical and conservative about the medicines I take?” The question may have been directed at the other person in the room: Rajeev Thakkar, his CEO and fund manager at the eponymous brokerage and financial advisory firm, Parag Parikh Financial Advisory Services (PPFAS), but it seemed almost rhetorical in nature.

Parikh is in the pink of health. Years of daily meditation have helped him look a lot younger than most people his age. And it might also help him deal with his next big challenge as he approaches an important crossroad in life.

Over the years, several hundreds of wealthy individuals have sought him out for customised advice on where to park their money in the equity markets. His trademark scepticism and conservatism have positioned him as a responsible and a relatively safe haven for investors. And the portfolio management scheme (PMS) he ran, where each individual investor has his own separate account, has had an established track record of delivering consistent and above-average returns. Over the past decade, it has generated a compounded average growth rate (CAGR) of 21.16 percent, beating the 16 percent growth in the Sensex during the same period.

He could have continued this winning streak, if it weren’t for the new law that allows only investors with a sizeable corpus—a minimum of Rs 25 lakh—to be part of a PMS. All other retail investors now need to invest in equity markets through the supposedly safer route of a mutual fund scheme.

For Parikh, that would mean a life-defining change. Parikh has had a simple motto since starting PPFAS: He preferred targeting regular retail investors who aspired to break into the bulge bracket. But that wasn’t the norm. Most other PMSes, such as ASK run by another marquee money manager Bharat Shah, ask for a minimum threshold of Rs 1 crore from every investor. Parikh, instead, asks for Rs 5 lakh.

Since Parikh’s is the first example of a PMS morphing into a mutual fund, it is being watched closely across India’s equity markets. Those who’ve known him say he should be able to retain most of his investors, who make up the Rs 330 crore corpus that his firm manages. “I know Parag Parikh for a long time. He is a value investor and a long-term investor and very focussed in investing. He is a person with strong convictions and is completely research oriented. He doesn’t get carried away by market moves,” says Motilal Oswal, chairman and managing director of Motilal Oswal Financial Services, a leading brokerage.

Yet Parikh will now have to move out of the relatively obscure world of alternative funds (as PMSes are sometimes called) into the hyper-competitive mutual fund industry. The dynamics are somewhat different. We’ll get into that in a bit. The moot point is whether his current base of investors—and potential ones—will eventually settle for a one-size-fit-all solution to their investment needs. Or will they continue to insist on individualised solutions?

On his part, Parikh has developed a differentiated strategy that he believes might help him carve out a niche in the company of the big boys of the mutual fund industry like HDFC, ICICI and Reliance. “The mutual fund will allow all kinds of investors to invest in our scheme. The idea is to make normal investors into high net worth individuals (HNIs). I don’t want HNI clients and grow their money,” says Parikh.

The big bet

Parikh has been looking to start a mutual fund for a long time. He had applied for a licence three years ago, which has now turned into a reality. Over the years, he has shuttered his debt market division in 2004 and then his institutional broking business in 2007, before concentrating on the wealth management business and the PMS business. Parikh has believed in lean teams with a tight rein on salaries and refused to be carried away by the euphoria of the markets.The work culture was remarkably different. His staff was never given any targets in terms of sales. Analysts were never forced to make stock recommendations, unless they were confident of their choice. And even fund managers were never forced to guarantee a minimum rate of return. Parikh actively discouraged intra-day trading and, instead, made his people concentrate on strong fundamental research, deep balance sheet analysis and direct interaction with companies. This work ethic helped nurture a generation of finance professionals who passed through the portal.

“One quality which is etched in my mind is his courage to stick to his convictions. He has, over a period of time, made trade-offs in terms of what he thinks is best for his organisation, in line with his beliefs—which is admirable,” says Vikaas Sachdev, CEO of Edelweiss Mutual fund, who worked with PPFAS way back in 1994.

Much of the heavy load is managed by Rajeev Thakkar, a level-headed, soft-spoken manager known to keep his cool in any situation. He has been with the firm since 2001 and understands Parikh’s temperament. This chemistry is crucial because Parikh is known to be an extremely demanding boss.

Thakkar will be the pivot around which the new mutual fund will revolve. Perhaps in line with their convictions, the duo has decided that there will be only one equity scheme. Here, 10 to 30 percent of the portfolio will be invested overseas, especially in the US markets. It is an all-cap scheme that will be benchmarked to the S&P 500 index. The scheme is categorically meant for long-term investors who have an investment horizon of at least five years.

Parikh and Thakkar have also laid down a guideline for staffers: They have been nudged to channelise all their personal investments in equities through their own scheme. The duo themselves plan to invest regularly into the mutual fund scheme in their personal account. “Though this is not a rule, we want to show that we have our skin in the game,” says Thakkar.

Now, this isn’t the first time that mutual funds are crafting such a policy. But the fact is very few rival funds state it upfront. This will be the first mutual fund where the top management will disclose their holdings in their own scheme on their website. Much of this draws from Parikh’s personal convictions about how money managers need to behave with customers.

The Moorings

Parikh started his career in 1979 as a sub broker and then took the BSE membership in 1983. In 1994, he took up space on the first floor of the Great Western building, a heritage structure opposite Lion’s Gate, near Colaba in south Mumbai. From the start, the office retained its old-world charm with its quaint furniture and relaxed environment. This is where Parikh first set up his cutting-edge research department, a one-of-its-kind investment research outfit in those days, to attract institutional investors.By the time Parikh had set up his PMS in 1996, he had developed a formidable reputation for being a straight-talker who believed money managers weren’t sufficiently focussed on serving the needs of customers. Even at the start, he insisted on attracting customers who had Rs 5 lakh to invest, while most competitors demanded Rs 25 lakh.

Like his investing guru Warren Buffett, Parikh prefers to stick to value investing. That means he picks companies where the business is simple and easy to understand. This is the main reason why he took a huge fancy to the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) industry. FMCG companies like HUL, Colgate and many other multinationals were listed in the Indian markets since the 1980s as subsidiaries of some of the biggest consumer packaged goods giants in the world. They had a good distribution network and were almost recession proof. For instance, he purchased Indian Shaving Products Ltd (ISPL, which later became Gillette India) in the early ’80s at around Rs 21 and sold it after 29 years at a price of Rs 1,900, a return of 17 percent per annum. He bought Hindustan Lever (now HUL) at the IPO price and has recommended the stock ever since.

Over time, prices of FMCG stock have risen exponentially. Today, many of them trade at a price-earnings (P/E) multiple of about 45 times in the Indian market. Parikh has been advising his clients to buy the stock of the parent firm in the US market, which is available at a P/E multiple of 15 times. “The idea is to buy the parents, which have an exposure to many markets like India. We get the parents cheaper than the subsidiaries and it is a great opportunity not to be missed,” he said.

Even for his new mutual fund, the same philosophy will come into play. Thakkar feels companies like Google and Amazon understand how technology can change the world. He has been advising his clients to invest in Google at around $400 since 2010. He feels that some of these technology companies have created high entry barriers that are difficult to breach. “Besides, you don’t get sectors like defense and aerospace or for that matter oil exploration companies in the Indian markets. We just want to expand our sectors by moving into other countries so that we have a well-diversified portfolio,” says Thakkar.

Notwithstanding his razor-sharp acumen, Parikh has had his share of nightmares. Like many value investors in the Indian markets, the technology or software boom of the late 1990s turned out to be a particularly difficult period for the firm. Parikh chose to stay out of the massive tech rally, where stocks like Infosys were being quoted at a P/E multiple of 100 times. His basic philosophy of not investing in sectors that he did not understand wasn’t well-received by his clients. While the rest of the market was besotted with software, Parikh was advising clients to stock up on FMCG. Many of his clients actually started leaving him because they thought they were missing out on the rally.

“During the tech boom in 1999 and 2000, all conventional wisdom was going down. There was the advent of the new economy. I did not understand it. Every day tech stocks would go up and I would go into depression. And then I started to look for answers,” says Parikh.

The ‘aha’ moment

He came across an advertisement in The Economist about a course in Investment Decisions and Behavioral Finance offered at the Kennedy School in Harvard University. He took up the course in 2001. That course turned out to be a life-changing experience and gave Parikh a whole new insight into the emerging science of behavioural finance. Here he attended the lectures of Richard Thaler and Christopher Browne, a well-known, successful value investor from Tweedy Browne managing more $10 billion. Some of these lectures used to go way beyond 10 pm throughout the course.Upon his return, he began putting his knowledge to practice. He learnt that patience is the key to all investment decisions. “I was able to eschew greed and conquer fear,” he says. Rajeev Thakkar says behavioural finance helped them to become unemotional while taking investment decisions. No more was he afraid to sell stocks and remain attached to them even when the valuations were high.

By 2002, the tech boom had ended. Many IT stocks had lost half their value. And there were rich pickings everywhere. That’s when Parikh decided to take a bottoms-up approach to investing. Thakkar and Parikh went back to clients and encouraged them to invest in the PMS. The bets worked. They got a similar opportunity again after the global financial crisis. Even when the markets have been flat for the last five years, the PMS has returned 14 percent annually.

The transition

On the face of it, there are clear advantages in morphing into a mutual fund.Right now, Parikh works out of a single location. Any customer who has to open an account with the firm will have to travel to the Great Western building in south Mumbai to do so. But with an MF structure, the fund can leverage the branch network of the registrar and ride on that.

Investing in a PMS is also a tedious process where the investor has to typically sign five different kinds of agreements. Besides, investors also have to show these investments in the books of accounts while filing their income tax every year. In a mutual fund, there is only one single form and there is no need to maintain a separate book of accounts.

Besides, for the investment firm itself, as the number of clients increase in a PMS, the sheer complexity increases manifold.

However, it isn’t quite as simple running a mutual fund either.

Competition is cut-throat. There are 44 registered mutual funds in the market jostling for space. All put together, there are thousands of mutual fund schemes on offer. (see graphic on page 43). And unlike the personalised nature of the PMS business, the mutual fund products are sold by an army of 10,000 brokers and sub-brokers. So any new fund will need to figure out how to stand out in the clutter—and also build distributor loyalty.

In the past, smaller mutual funds like Benchmark and Quantum have figured out a way to remain profitable by bringing something new to the table. Parag Parikh is banking on his long term value investing format with a touch of behavioural finance. The key to success will, of course, be performance.

And while Parikh’s personal brand equity is strong, it may take a while for distributors to see value in pushing his scheme over that of the traditional leaders like HDFC and ICICI.

Parikh, of course, has his own inimitable style of signaling his intent. In his prospectus, he plans to advise investors to stay away from his fund unless they stay invested for a minimum of five years. Equally evocative in his logo: A green turtle.

The original article could be seen here.